A Year in Review: 2020

I’ve never been drawn to the prescriptive nature of a year in review—but this year it feels useful to look at what we’ve gone through with the hope that we can leave the precarity behind.

In January, while aware of the virus but unaware of its coming impacts, I mounted a group exhibition at General Hardware titled fossil record. Freshly grieving, my curatorial statement had a tinge of sadness to it—my desire to define the line between permanence and ephemera still feels pertinent. What of this year will become permanent fixtures? Our anxiety toward touch? A clearer sense of the structural conditions that lead to inequality?

I’ve been thinking lately about the thin line between permanence and ephemera. Plants, flowers, performance, feelings, and life are all in a constant state of decay, only lasting a short period of time before they’re gone. The only things I can think of as permanent are plastics, literature, and art. The latter tries to grasp onto the concept of decay, translating the ephemeral into something permanent. As the world changes around me—people die unexpectedly, relationships fade, a favourite piece of jewelry is misplaced—I take comfort in art’s ability to anchor me in a world that doesn’t make sense.

Art continues to fill that role for me. Living with art this year grounded me, kept me company, and allowed me to connect with others. I’m interested in the connection and closeness we feel towards art without having to touch it. In fact, not touching allows us to care for it more, ensuring that it stays safe for generations to come. Our relationship with art—the ability to touch with our eyes and feel close without contact—has primed us for a year with a lack of human touch. My strong belief that art can act as company and brighten our mood is what led Margaux Smith and me to start Canadian Art in Isolation, which donated art to seniors in long-term care homes, which you can read about here.

The way artists mobilized, again and again, this year proves that care is foundational in the practice of their work, reflecting in the aura of the art itself. “Consider the way artists stepped up, quickly donating work for fundraisers to assist hospitals and marginalized communities, as soon as the pandemic became widespread,” I wrote in an essay for the opening of Patel Brown Gallery in the Spring. “Shows that were swiftly canceled or postponed were shared eagerly by fellow artists on Instagram feeds….The point I’m trying to make is: artists know care. It’s embedded in the very practice of what they do,” I continued.

I hope that the articulations of care, through non-monetary support as well as buying art from emerging artists, is something that becomes a permanent fixture in the art world. If the advent of these initiatives was born from necessity, hopefully, it can morph into a routine.

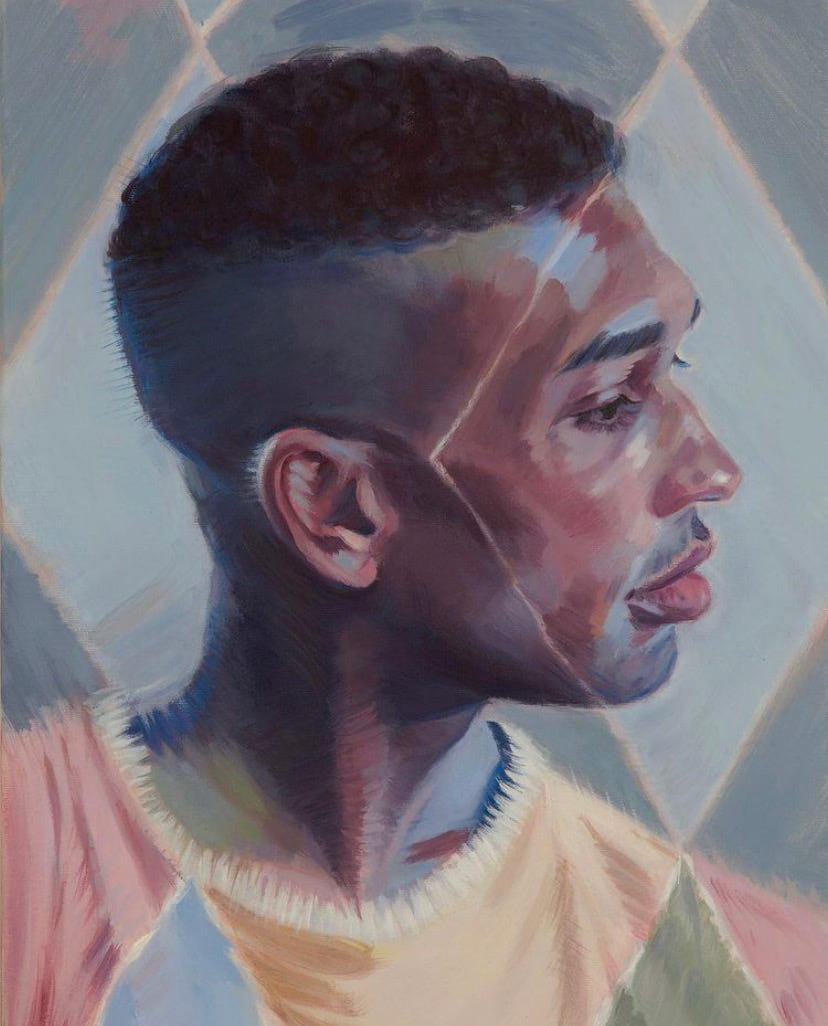

In May, George Floyd was killed by police officers in Minnesota. The grief of living in a pandemic was compounded to an unbearable degree. Why did it feel like the world’s atrocities should pause while we dealt with a communal hardship? The truth is that the pervasive structures of white supremacy and police brutality are never latent—only ignored. With millions of people protesting all over the world, it was now impossible to ignore.

The structures that allow such atrocities to happen are present in the art world—seen through a lack of representation of Black and Indigenous artists, as well as overt racism and micro-aggressions. Galleries responded to this reality by posting black squares and statements promising to do better (the former felt performative, the latter at least had the potential for introspection and improvement going forward). Not knowing how I could be helpful in these conversations, I started a spreadsheet of Black and Indigenous artists, which people have continued to add to. The point of the list is to say: there is a surplus of talented Black and Indigenous artists in Canada, so there’s no excuse not to support them, represent them, and buy art directly from them.

Our attention has pivoted a few times since then—with promises of a vaccine, a new president in the United States, as well as the stress of our day-to-day lives—and the conversation shifted away from white supremacy and the Black Lives Matter movement. Have things changed in the art world? It’s too soon to tell if the posts and mandates were performative or not—but we should continue to hold institutions accountable, outside of news cycles, on a permanent basis.

If anything, this year has shown that collective grief, and articulation of said grief, can create change. Hopefully, these changes are permanent, with the pain that caused them fading away towards ephemera.

I’ll be taking a bit of a break from the newsletter over the holidays—but am always available to chat over email if you have any comments or suggestions: tatum.dooley11@gmail.com

I am wishing everyone a safe and happy holiday season.