An Afternoon with Sirius Glassworks

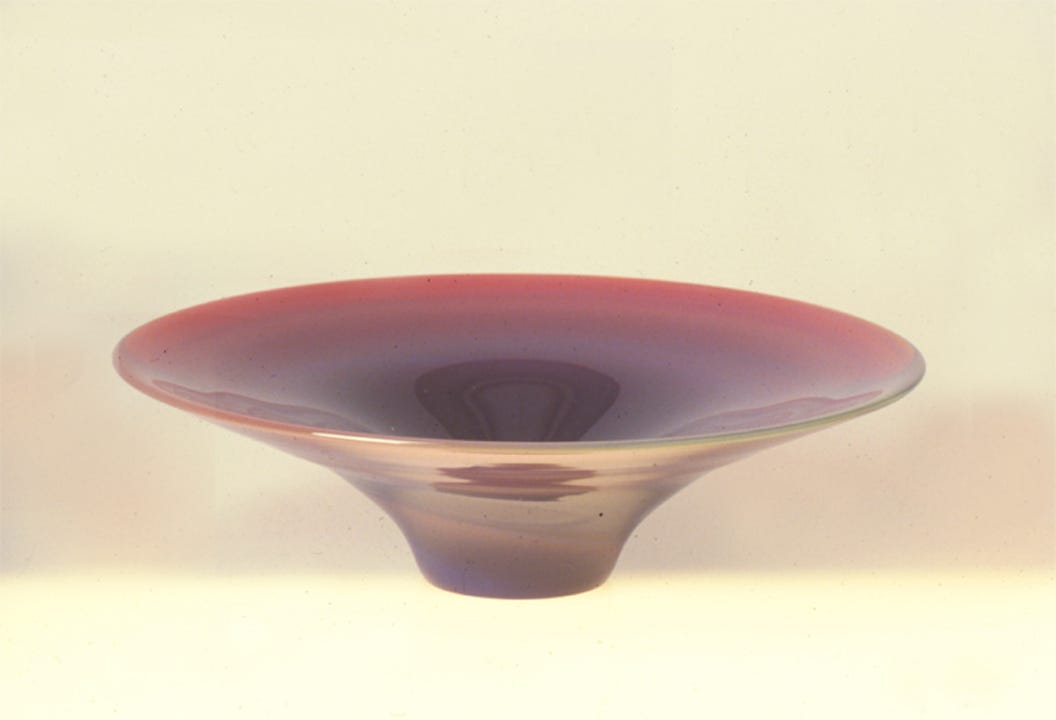

Whenever I’m feeling a little sad, the glass blowing hallway at the Harbourfront Centre lifts my mood. Something about the pungent smell of burning glass, the heat, and the mesmerizing methodical steps of the process put me at ease. I could stand there for hours. Likewise, the feeling of drinking a glass of a water from a handblown vessel automatically elevates the act into something meaningful. The weight, vibrant colours, and uniqueness of the object transmutes a glass into a meditation.

In other words, I consider every step of glassmaking to be a work of art. Sirius Glassworks, a studio in Gasline, Ontario, makes glass objects that look like painted sculptures. Their vessels are worthy of heirloom-status.

I chatted below with Iris Fraser-Gudrunas, the studio manager of Sirius Glassworks, about the family business and the collaborative process of designing glassware that her father, Peter Gudrunas, makes. In the course of the interview, I learned a lot about the care and attention that goes into making glassworks. I hope you do too!

Tatum Dooley: Can you give a brief history of Sirius Glassworks?

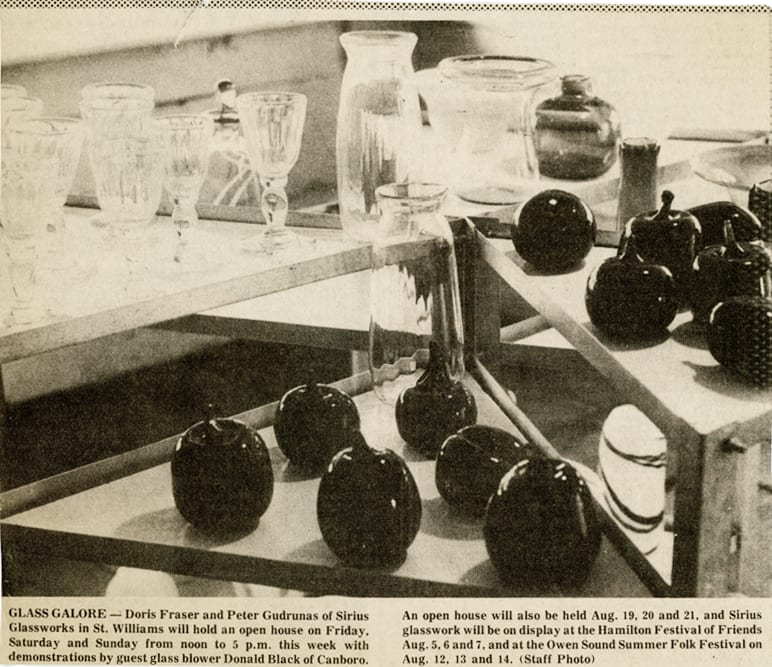

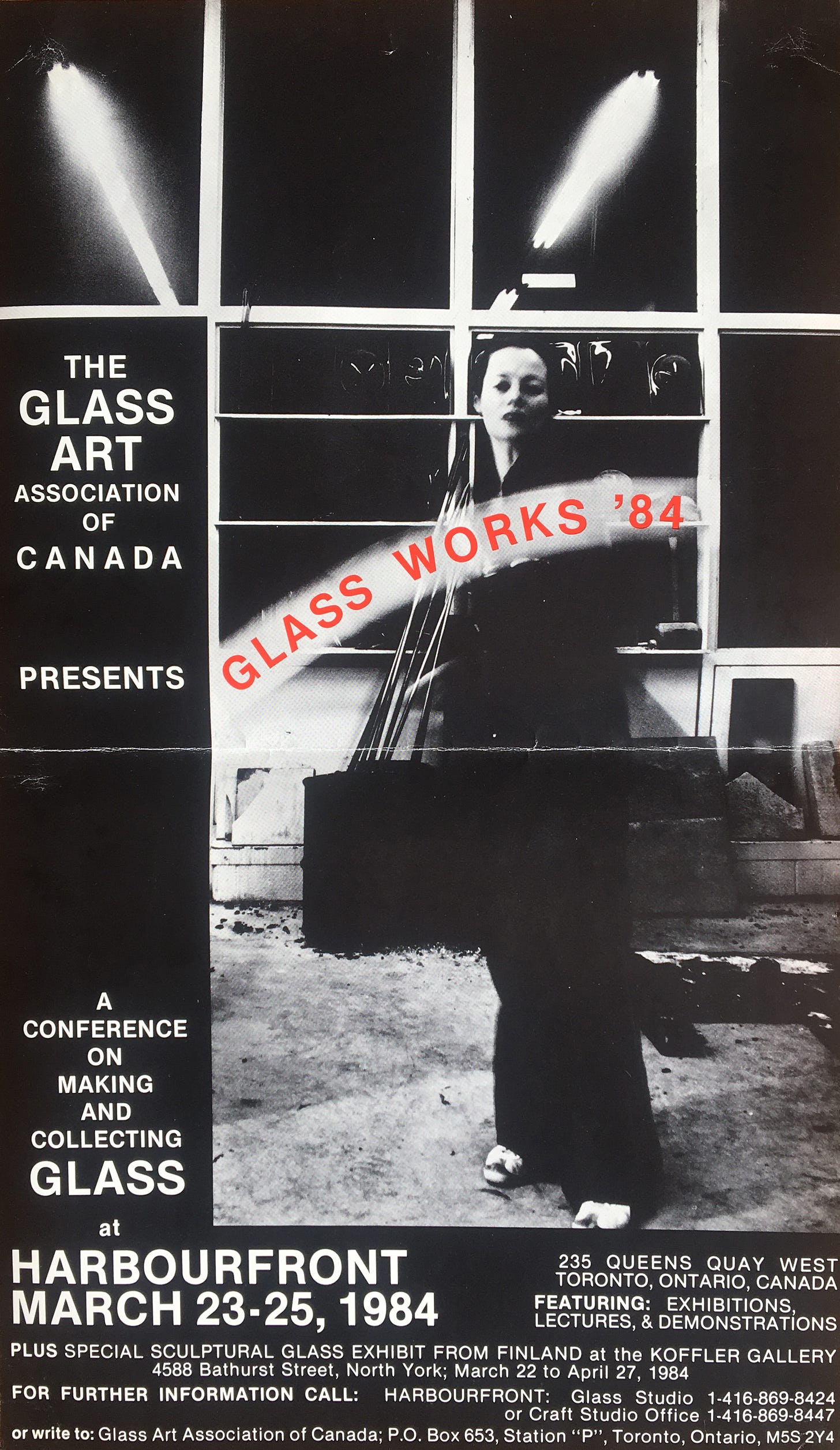

Iris Fraser-Gudrunas: Sirius Glassworks was started in 1976 by my mother and father, Doris Fraser and Peter Gudrunas, at the forefront of the craft renaissance and Canadian Studio Movement of the late 60s and 70s. Studio glass began in Canada with two initial teachers and my father was one of the first five students to take classes in the medium in 1972. He met my mother a couple of years later at Georgian College while she was teaching interior design and colour theory, and taking the glass program in her spare time. They opened their first studio practice in 1976 in Brantford inside a former brick kiln. They moved to Gasline, Ontario in 1982 where my father's studio has remained for the past 39 years. In the early days, there was a lot of peer to peer learning and experimentation between a small group of 30 people that made up the first generation of studio glass artists. My parents hosted an annual Glassblowers Picnic which was a place to skillshare. They both participated in the founding and formation of organizations such as the Glass Art Association of Canada. My father has been running Sirius Glassworks as a solo studio since 1986 and has been one of the few people on a private scale to make his own glass colour from scratch. I stepped in as the Studio Manager and designer in 2013.

TD: What does the collaboration look like between you and your dad?

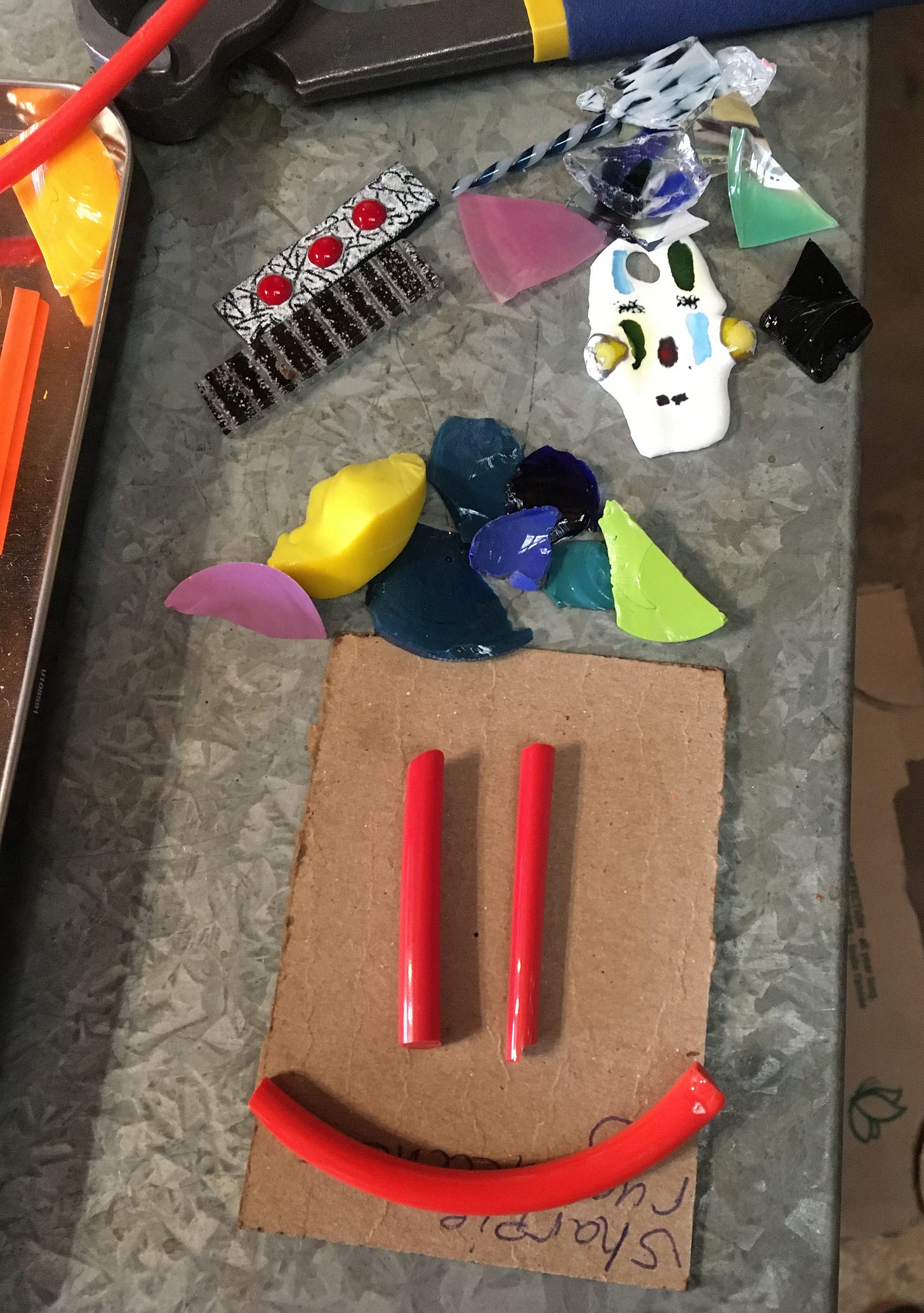

IFG: A lot of the collaborative aspects revolve around me coming up with a colour palette and decorative style, conceptualizing a technique for a series, and going over the techniques with my father. I often give input on shape during the process of forming the piece, or else I leave my dad to execute the series however seems best to him. If it's something like tumblers, I might sit in for the first few to make sure the concept is working out, help troubleshoot changing the method if it's not working out, or just cancel the concept if it turns out to not be achievable. If they're more complicated tumblers I'll sometimes assist by laying out the colour decoration on a canne warmer for each piece and then placing various punties and blowpipes in various buckets and open the door to the annealer when the time comes. When we've done casting projects my sister and I both assist, I handle the molds as my dad pours the molten glass. We often start with a goal in mind for the type of shape I'd like for the piece but sometimes we have to let the glass itself choose what shape it wants to be.

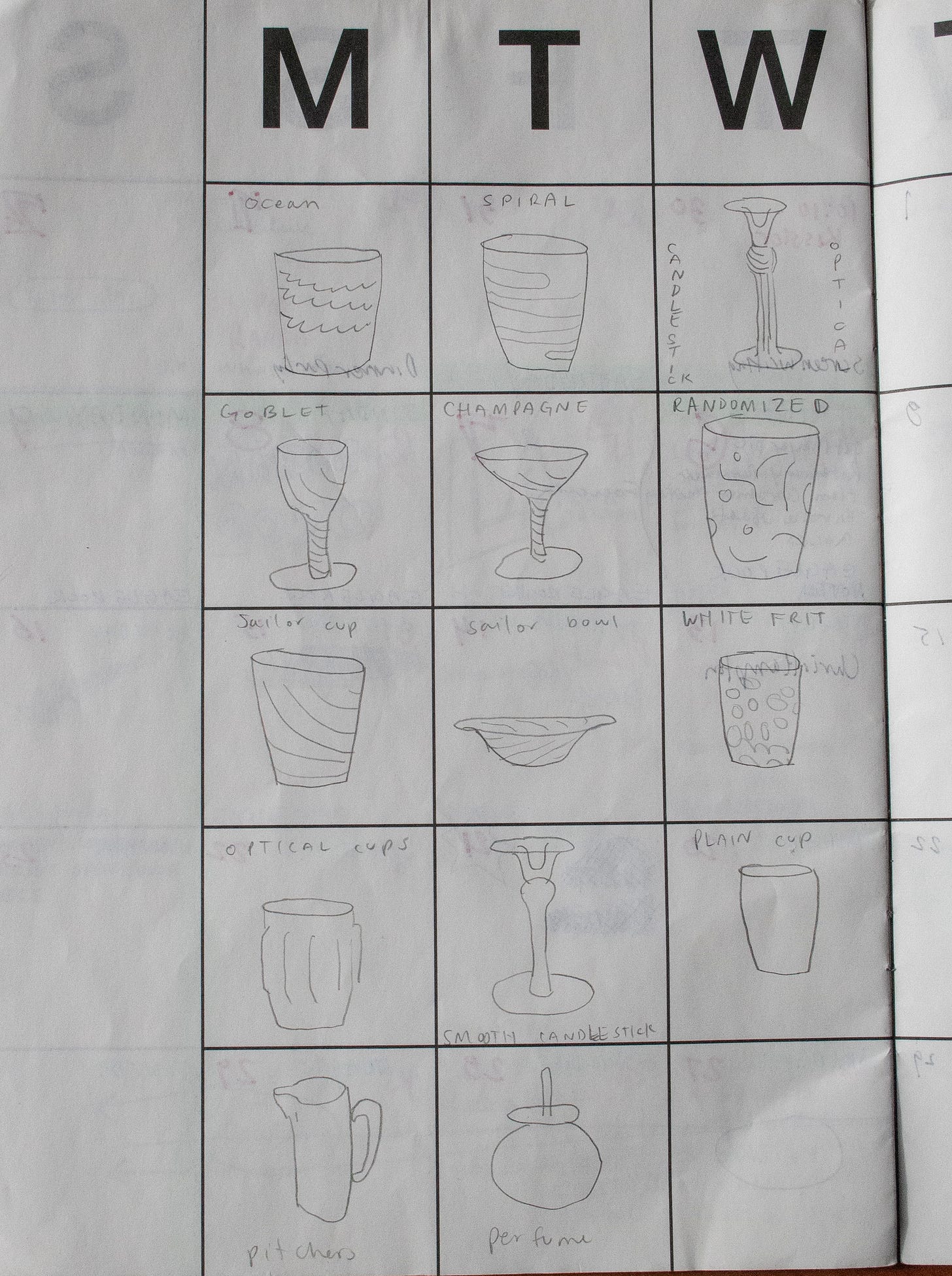

TD: What's your process for designing glassworks?

IFG: I drew a lot of creative direction from the process of sorting through [the archives from the 70s, 80s, and 90s] and revisiting materials and shapes that hadn't been used in the studio in a long time. I also have my own collection of glass that I refer to and there are some shapes that I personally just like more than others so that influences my designs as well. But a lot of my design has come from working within the constraints we face as a studio. My dad is one of the few people in North America to melt his own proprietary glass 'system' and colour from raw minerals. Most glass needs to be a part of a 'system' to guarantee it fits. That means that if two types of glass are fused together but have different ratios of minerals in their recipes, they won't fit each other because their molecular structures are different and they will cool and expand at different speeds and crack.

[The Nassau designs] were named after a street in Kensington Market where I used to live near artists Laura McCoy and Sandy Plotnikoff. When I lived there in 2004 it felt like a hub, it was very vibrant. I had this large box of broken colour bits from a glassmaker in the next town and it reminded me a lot of Sandy's studio full of all these colourful bits of foil that he repurposes into larger works. So the Nassau style came to be. I would fish through this technicolour detritus and pick out a handful of shards that I liked as a combination and then we would encase them in clear glass. The Nassau series and the random canne style are ones we keep revisiting because they're super fun to make, exciting to look at and there's a lot of great responses. I'm starting to experiment a bit more with concepts but also love still working our way through barrels of cullet and designing new shapes or methods to make a single colour more exciting.

TD: I've noticed your glasswork everywhere lately—they're sold at boutiques in Toronto, on the Instagram feeds of popular It girls, and the Nassau tumblers sell out almost immediately—do you feel like there's a resurgence in handcrafted work? How do you account for the popularity?

IFG: I started to notice a building interest in historic fine-craft ceramics around 2010ish. I knew it was a matter of time [that people were introduced] to glasswork. I think the 90s art-glass aesthetic can be was not on the scope of desirable aesthetics, but I truly believe in collective unconscious towards trends and the recycling of aesthetics. My sister and I have been doing these glass sales of our Dad's work for over a decade so we've been building an audience of fans that has spread via word of mouth.

There's a lot of glassmakers that strive for symmetrical perfection, but after we started getting so much response from people wanting the more unique and asymmetrical pieces or the rare one-offs of colour or decoration, we changed the ethos of production and began embracing the fluid nature of the material. I think that's what makes the Nassau Cups and all our work more covetable; you can feel it's handmade, and you absolutely cannot confuse it with something made industrially. I also think hand-craft has become more desirable because there's a broad swath of our generation who started their adult lives enveloped in IKEA housewares. We're also a generation that cannot afford the housing market, so I think having beautiful small objects helps a lot of us build a semblance of a home that feels unique to us. It's like, instead of being able to control the container, we can control the contents. And who wants a reflection of ourselves that's made of Ivar shelving and disintegrating melamine covered particleboard?

TD: What does the glasswork community look like in Canada right now--how would someone get into it?

IFG: Of the generation of glassmakers my father started with there are a few studios still operating including Ione Thorkelson's, Robert Held's, and Ron Lukian's, but many have retired or passed away. I'm more familiar with the people that overlap from a fine-arts practice. I love Kelly Akashi's work, she's a friend and has done a studio residency at Sirius. And Kara Hamilton is another amazing artist who has worked in glass. I also love Fin Simonetti's stained glass work which is very refined, skillful, and thoughtful. I was recently shown Grace Wardlaw's torch work and it's very beautiful. I know the major programs are at Sheridan and Fleming College, or for people who want to get into it without going back to school full time, Harbourfront Centre is a really good starting place. Pilchuck in Washington State is also a place that artists can apply to do collaborative residencies. It is still very niche, and quite jocular. It's such a rigorous and steep uphill climb to build skill that you have to be super committed to it. I would definitely love to see more women and queer people in the glass scenes.

You can follow Sirius Glassworks on Instagram here. Visit their website here.