I’ve written before how my love of art is, in part, due to its permanence. As we live in a state of constant flux, art is dependable and unchanging. Going to a museum often feels like visiting old friends and when I look at the art on my walls, I imagine my whole life living alongside them. This act of grounding through art brings me comfort and joy—in the familiar, in the historical, in the tangible, in predictability.

Of course, art is not always permanent. It erodes and dulls with time, especially when not cared for properly. Due to my love of art and desire for permanence, I reached out to Monique Palma Whittaker, an art conservator, about her practice. I was taken with how passionate Monique is about caring for art, about the importance she places on both conserving historical art for the present day and caring for art so that it can be propelled into the future.

“It’s important as a collector to remember that you are now a steward of the artwork—your job now is to take care of the artwork is stable and healthy for the future and for the cultural zeitgeist. We need to protect our artwork. It’s a stewardship rather than equity or ownership,” says Monique.

The distinct quality of merging past, present, and future in art conservatorship makes for a distinct way of seeing art—one that Monique shared with me below. Stick around till the end of the interview for simple tips of keeping your art safe for generations to come.

Tatum Dooley: I’m wondering how you got started as an art conservator?

Monique Palma Whittaker: I knew I was interested in art conservation in high school. I was a big art kid but I was also really interested in science as well. It wasn’t until I was in my undergrad, in my hometown in Guelph, Ontario, and there’s this really beautiful basilica that was under restoration and the lights really went on for me. I was like “oh my goodness I can weave my interest in painting and art and science and history all into one cohesive career path.” So I started to focus my education in that direction. Once I completed my BFA at Concordia I did my chemistry prerequisites, which I also did at Concordia, and then I went onto do my graduate studies in painting conservation in Florence. It’s something that I’ve always been attracted to and I like the idea that I’m not necessarily making anything new but I’m helping to propel these historical artworks into the future so that people can enjoy and study them.

TD: Do you specialize in anything specific—I know you do a lot of work in churches, but is there a specific project that you really enjoyed working on?

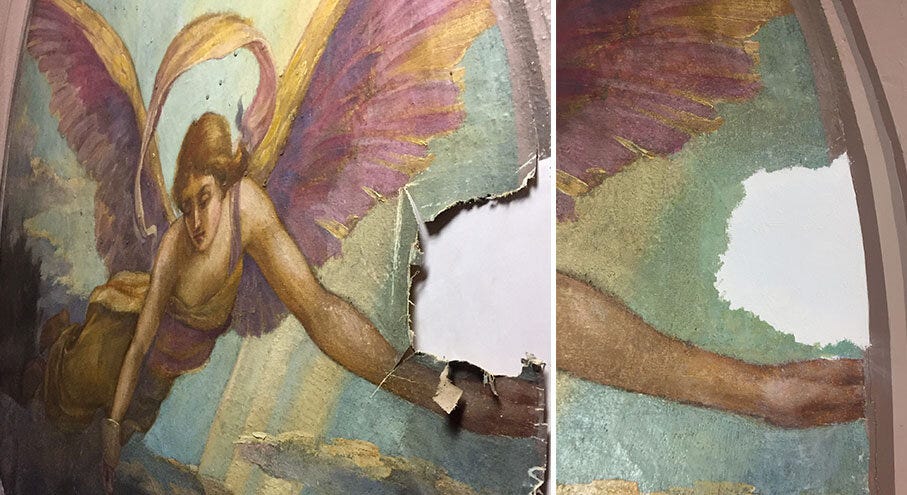

MPW: I’m trained as a painting conservator, we tend to think of that as oil paintings on canvas or wood panel or mural. Basically, anything that has pigment and binder and support is something that I’ll approach. However, for me personally, I really love working in situ. I love being in a different environment, being out of the studio, climbing scaffolding, really getting to see the artwork up close from a very different vantage point than most people.

TD: I think a lot about looking at art—it’s always at this respectful distance at art museums, you’re not allowed to touch or take photographs. I wonder if you feel you have a more intimate relationship with the art because you’re able to touch it and be closer to it?

MPW: It changes the way I navigate and experience art in a museum or on the street because I know how intimate these relationships with art can be and I’m so interested in the materiality of things. For instance, if you’re restoring a painting that’s thirty feet in the air, I’m going to see details that no one gets to see. It’s so exciting, it feels like an unveiling of sorts. Even in different architectural settings, you’ll see often the tradespeople who built the church engrave their names onto the ceilings. It’s this really special moment you get when you’re working as a conservator on-site to see the people that have come before you and things from the ground level you’ll never see. You can’t be afraid of the artwork, you have to get up close and personal.

TD: On that note, of being afraid of the artwork, there have been a couple of instances of botched art restoration in the last couple of years, like the ‘Monkey Christ’. I wonder what your take is on that.

MPW: As a conservator, it’s horrible. Horrible to see a historical artwork get ruined that way. The principles that govern the way I work is everything I do has to be minimal, you employ the most minimal interventions possible to conserve the artwork. You also want the materials you’re using to be reversible so that in the future if there’s better technology, or science, or materials it can easily be undone. Then you also want to do something that is minimally invasive. So to see these botched restorations, they’re so comical, but obviously it’s pretty devastating to see original art ruined. To me what is so wild is how far they go off the tracks—they really surrender to it. In a way, it’s kind of advocating for the conservation and protection of artwork—training professionals correctly.

TD: What is the career path of an art conservator. Is there a gender divide? What’s it like owning your own business?

MPW: When I was in school for conservation a lot of the texts I was reading were from white men. But I have to say it’s a pretty female-dominated industry, which I think is pretty exciting and not surprising, women tend to be more caring and tender to objects. To go in this path you have to go into chemistry and find out what material you like, you can work in metal, paper, painting. Then you do your masters and continue your education. You can go either into the institution domain, where you’re working in museums, or private collections, or you can go into private practice. I personally really enjoy private practice because it’s very diverse and there are so many different things you can do, I think I’d have a hard time going to the same environment every single day.

The pros of institutions are you have endless budgets to do tons of different research and diagnostics—in the private industry not a lot of clients want to pay for additional forensics depending on the price of the artwork. I think the real kicker is to get experience and not being afraid to get your hands dirty and interact with the artwork.

TD: I’ve been thinking about preemptive conservation. I have this painting in my house that’s very dark and my cat’s hair gets all over the painting and my boyfriend just whips out a Lysol wipe and starts cleaning.

MPW: [laughs] No!

TD: How do you take care of your paintings at home so you don’t need a restoration down the line?

MPW: Just like medical science, prevention is key. If you can prevent an interventional restoration that’s great. The ideal situation is you control the humidity in your apartment, you try not to put the artwork on an exterior wall, if possible. If it’s a painting I’m a huge advocate for varnishing, I know in contemporary painting it’s fallen out of style, but varnishes have come such a long way you can really control the sheen that you want. So varnish paintings with a UV filter, that will always save you a headache in the long run. And don’t Lysol or Windex paintings! Please don’t. Just a dry brush, a sable hairbrush that you use to dust periodically. Try to keep it out of direct sunlight. Just caring for them, don’t put them in kitchens if they’re not framed, try to keep them out of bathrooms.

I’ve had to restore paintings that people have cleaned with Windex and it’s not nice, they just melt.

Thanks to Monique for sharing your time and expertise with us—you can follow her restoration projects on Instagram.

Does anyone have recommendations for painting restoration / conservators in San Francisco?