Exhibition text for Joy Walker's exhibition "Disruptions"

Joy Walker’s latest solo show, Disruptions, took place September 19 - October 24 2020 at MKG127. It was one of my favourite shows last year—and one of my favourite pieces of texts I wrote. You can read the essay I wrote about Joy’s practice below.

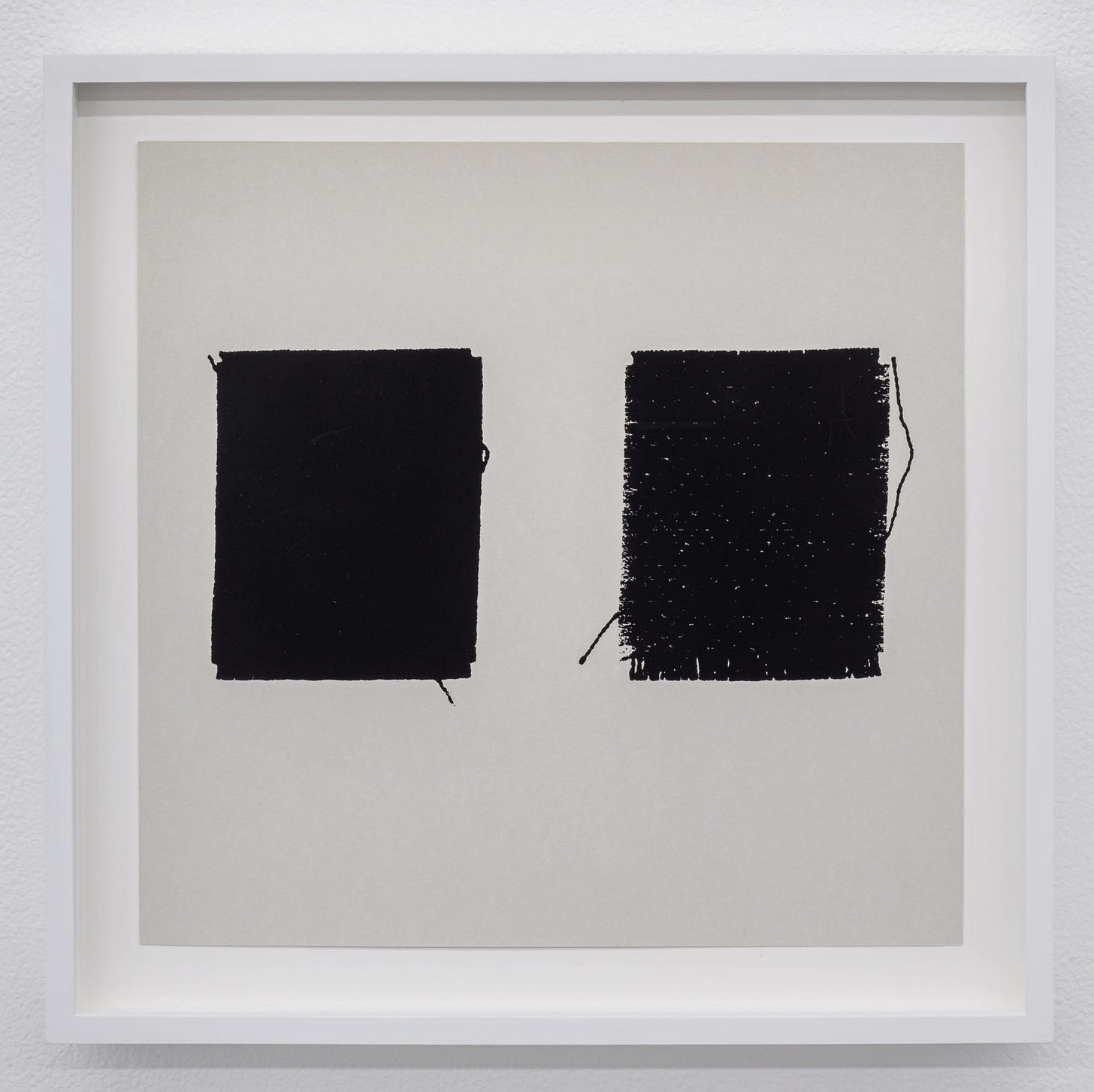

There’s a game of broken telephone happening in Joy Walker’s art. It starts with a painting whispering in a drawing’s ear the descriptions of a paint stroke. Then the drawing tells a sculpture, which tells a screen print. Finally, the screen print takes great pains to tell a textile what a paint stroke is: a length of colour, patchy in places, and frayed at the ends. Walker’s work acts as a translator from one medium to another, allowing things to get lost in translation with the knowledge that within that process, something is added as well.

Walker’s multi-medium approach references an array of artists, providing the viewer with multiple historical ways into the work. Frank Stella’s paintings, Agnes Martin’s drawings, Fred Sandback’s sculptures, Roy Lichtenstein’s screenprints, Anni Albers’s textiles. A journey through modernism, vis a vis the paint stroke.

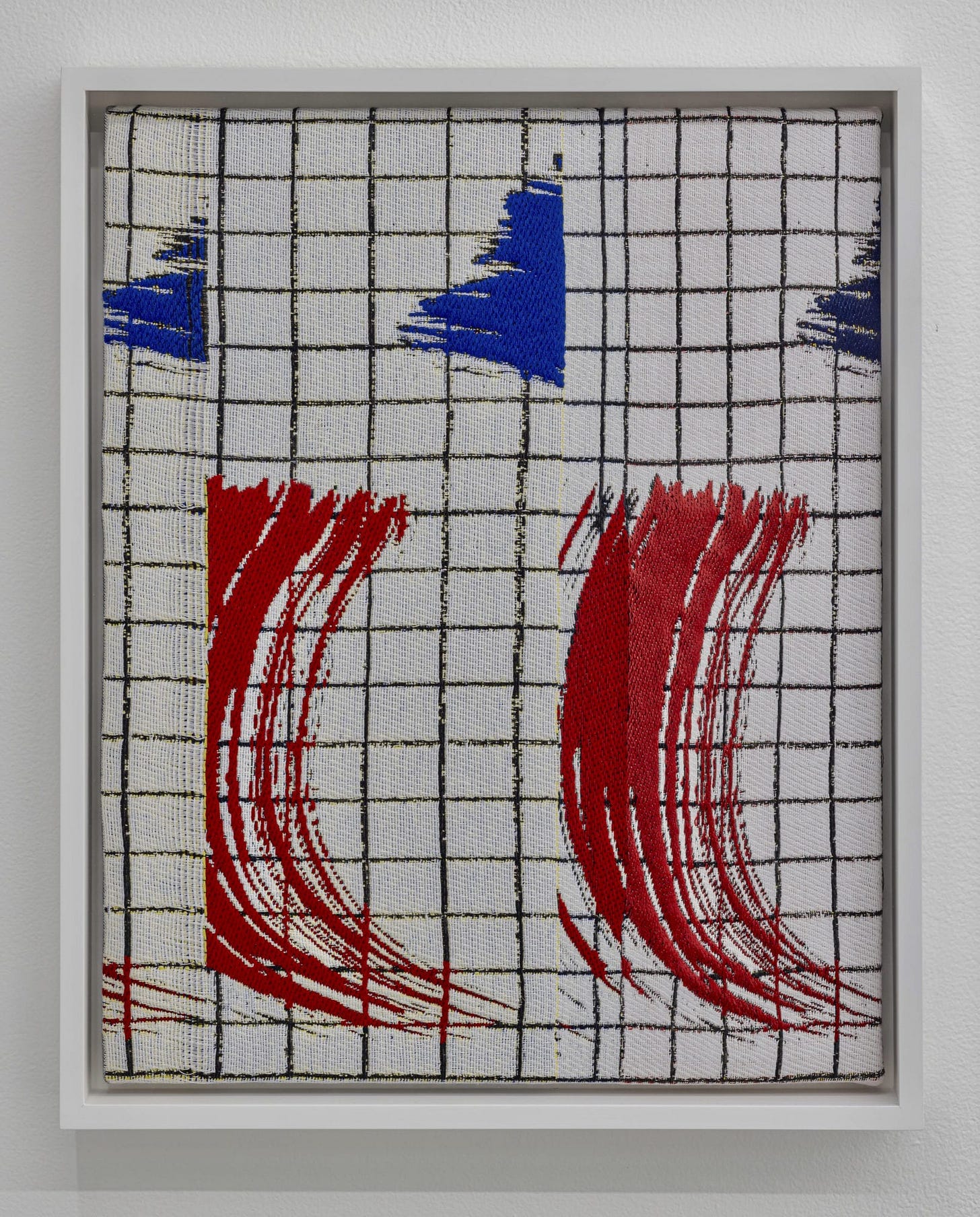

In Brushstrokes #1 (For the Women of the Bauhaus), a slightly out of sync grid is overlaid with trails of red and blue paint strokes, painted in thread instead of pigment. Similar to the way Anni Albers interjected freedom into the grid, slightly askew grids repeat in Walker’s work. “The grid is a predetermined, ordering structure that artists can choose to either follow or disrupt. Artists have both used and subverted the grid,” writes Alina Cohen in an essay for Artsy on the grid titled “For Artists, Grids Inspire Both Order and Rebellion.”

In an art world hierarchy, painting sits at the top and textiles near the bottom. Textile’s delegation as a craft, rather than medium, is due to its proximity to women’s work. Albers felt the classification of textile work as a feminine craft to be inherently misleading. Textiles necessitated planning and mathematical equations, the use of the grid, before beginning a weaving, characteristics that are typically seen as masculine. The combination of the structural grid and spontaneous paint stroke in Walker’s work create a pleasurable dissonance, one that allows a microscopic look at how materiality shapes our understanding of art.

Weaving’s inherent grid, made of warp and weft, is typically invisible. Not in Walker’s work, where the grid remains prominent. The invisible becomes visible. Walker visualizes the work that goes into weaving that’s overlooked and not often considered. The invisibility of the technical elements of weaving results in it being dismissed as a frivolous form of craft opposed to fine art, in other words, women’s work. This gendered dismissal is common in all parts of life, as well as it’s solution: make the work visible.

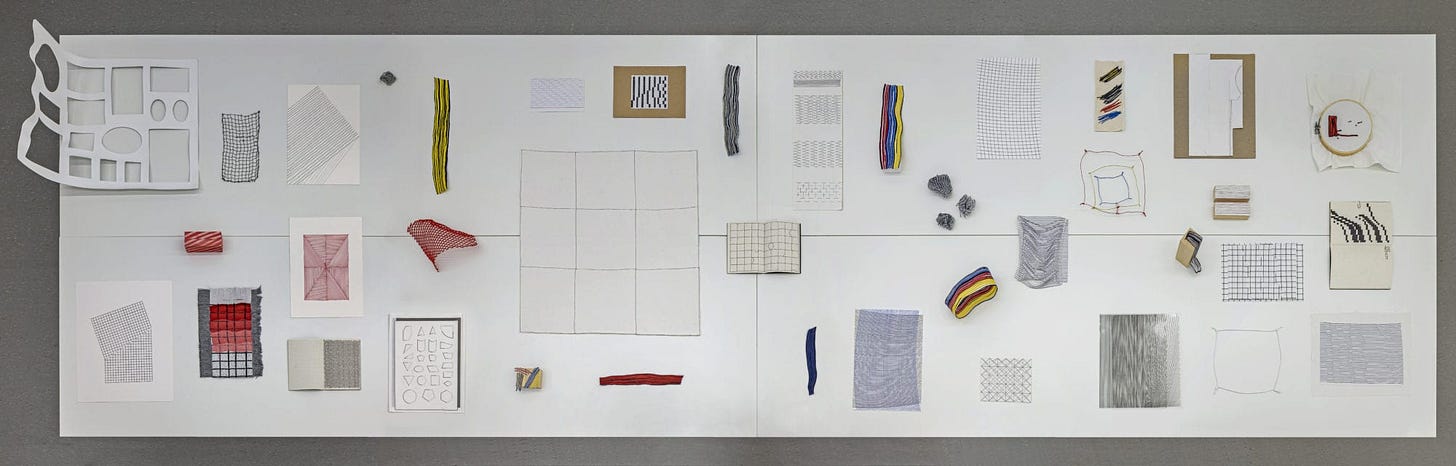

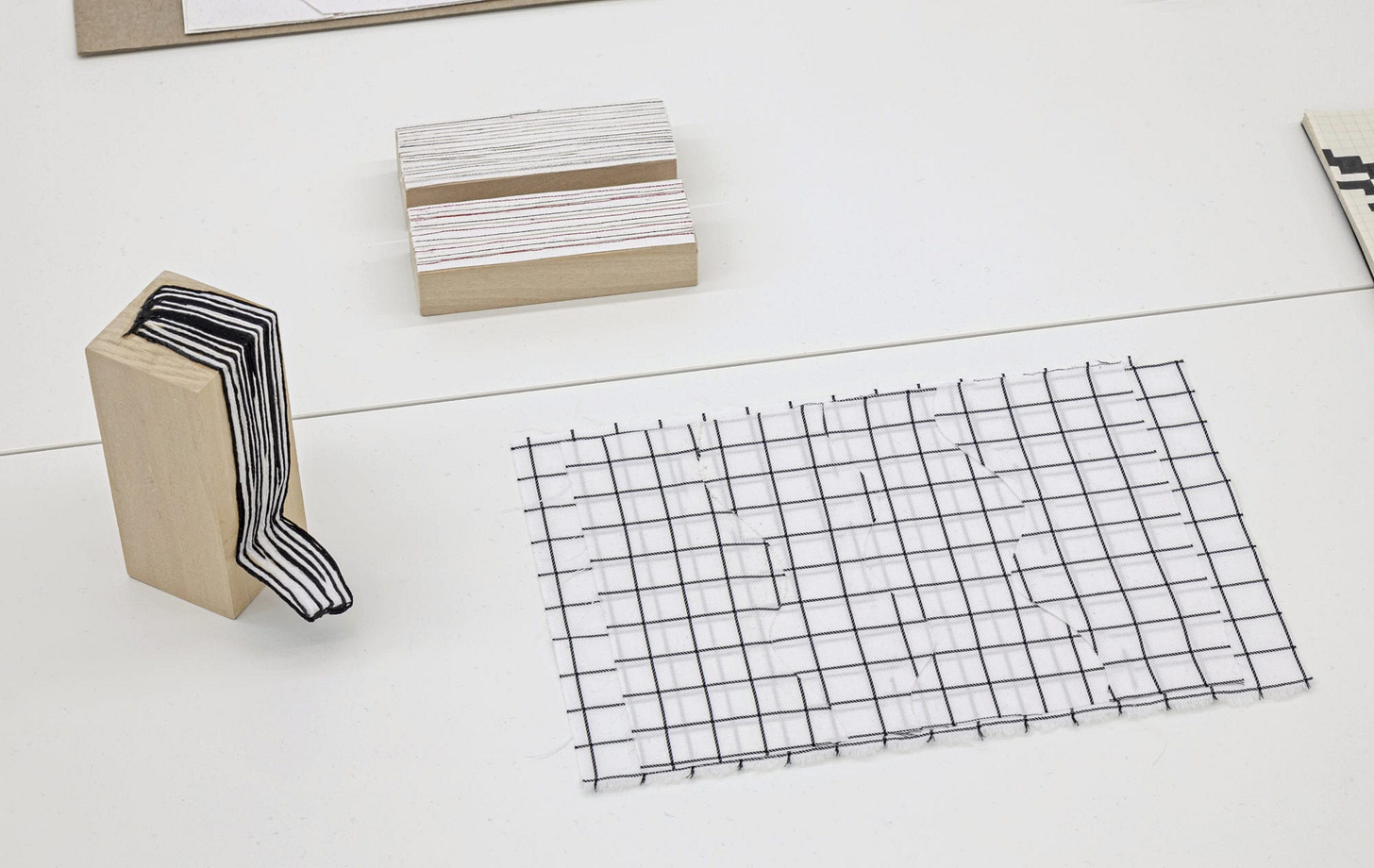

Walker’s tendency to show her process, as well as the focus on materiality, is in line with the Russian modernist Aleksandr Rodchenko’s ideal of faktura, which states that work should contain nothing more than its constitutive elements, its own mode of construction. Frank Stella and Lichtenstein followed this practice as well, the stripes of colour included frayed edges that gestured to the painting process. Walker’s inclusion of sketchbooks, paint strokes (including the frayed edges), and the grid in her work encompasses the ideal of faktura, where the process can’t be divorced from its final form.

All three elements—the sketchbook, paint stroke, and grid—are at play in Walker’s large-scale textile Untitled (Sketches #1). The work doesn’t read as a typical textile, where a pattern reaches each edge of the canvas, but instead transfers pages of Walker’s sketchbook into fabric. The result is a pictorial form of weaving, in keeping with Albers ethos of textiles as a form that’s potential is greater than repeating patterns. This inclusion of the process within its form replicates the inherent nature of weaving, where the design and surface are one in the same. “So while another weave—the canvas—provides the forgotten, or neglected, structural ground for painting’s content, the visual design of the tapestry cannot pretend to detach itself from, or supersede, the material through which it is made on a particular apparatus—the loom,” writes T’ai Smith in “Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design.” If a thread becomes loose, the image unravels and returns to its original form: a thread.

If a paint stroke is a trace of an activity, a hand pressing a brush full of pigment over a canvas, Walker’s art contains multiple traces of activities: the primary form of looking, copied into a drawing, translated into another medium, permanently embedded into the physicality of the work. The paint stroke becomes visualized, more haptic and aware than its original form. Instead of sitting on top of a white canvas (itself an overlooked form of weaving), it becomes inseparable from its form. Decades of visual texture packed into a single plane.

Follow Joy on Instagram here.