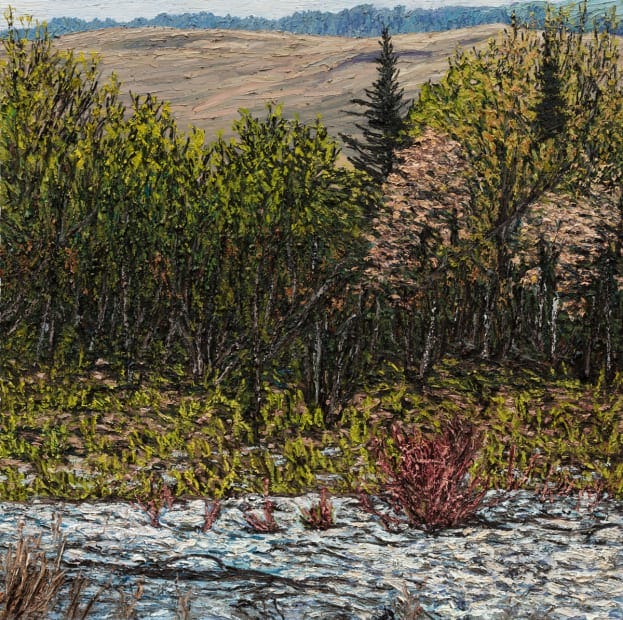

A couple of weeks after I saw Matt Bahen’s show “The Strange Garden,” at Metivier Gallery, I went for a hike in Elgin, Ontario. Less than 15 minutes in, I saw two horses. I was taken aback—how could there be horses on this part of a trail? Why weren’t they moving? As I got closer, I realized they were realistic plastic renderings, part of an educational diorama. The feeling was uncanny, it was an incredibly odd thing to come across. But not as odd as how warm it was for January. How little snow and ice—the prevailing reminder of the changing climate. I thought back to Bahen’s show, the disorienting landscape and the feeling of something being beautiful, but not quite right.

Tatum Dooley: How would you describe your painting? The texture is so difficult to understand in photographs. I wonder if describing them in words might get closer to the experience of looking at them in person?

Matt Bahen: I would say it's thick impasto that is evenly applied to the entire surface of the canvas. It's an all-over thickness.

TD: How did you decide on that application process?

MB: It's evolved over time, when I first started working in oil I was attracted to the thick paint from the earliest influences of Tom Thompson and Vincent van Gogh, just from looking at images and books, not ever having seen one, so you start with a facsimile of what you think the paintings would look like. As I matured, the all-over approach and the heavy paint became more of a conceptual element in the sense that I really wanted to pronounce the difference between painting and photography, because I use photo sources to make my work. I think photography has an element of journalistic truth about it, where painting historically has been allegorical. I've always wanted to have that at the forefront. So when people are looking at my work, they know that they're looking at a painting and painting isn't journalistic truth, it's allegorical.

TD: What is your source material for these paintings?

MB: Some people will send me photographs. Doing online searches. With this body of work, the Strange Garden, I'm taking the narrative device of the dark wood or the enchanted forest and I'm trying to create an image that has disparate types of landscape within it. I'm having a mountain range, but you're seeing the desert, but you're seeing a waterfall. Those incongruencies sit nicely at first glance, but the longer you look at the image, the more incongruities appear, and that's supposed to be a metaphor for the changing climate.

TD: When I visited the show, I was taken by the fact that, at first glance, you might just read them as typical landscapes. And then, after a while, you start to notice these inconsistencies that unsettle.

MB: I didn't want the paintings to be didactic, or to show catastrophe. When talking about, or trying to engage with, the issue of climate change, that tends to be the knee-jerk way to engage with it. So I wanted to approach it from a more narrative plane and use the tools of storytelling to engage. That's why I thought that the enchanted forest would be helpful in making paintings that people would want to look at and get engaged.

TD: How do your painterly references influence either the application of the paint or your compositions?

MB: This exhibition has quite a few more central compositions, there's an object in the middle and it's fairly symmetrical. I think the subject did influence that because that is a compositional type I would rarely ever employ. But it seemed that the subject and the imagery seemed to call themselves towards that type of composition. I'm much more accustomed to an asymmetrical composition to create tension. I think there was enough tension already within the imagery that I didn't feel like I needed to force it any further.

TD: Would centring the composition also have something to do with the use of square canvases?

MB: I'm using the square canvas to create the tension itself and to take the conventions of landscape and distort them. My use of high horizon lines has been consistent throughout many years of working. [As a way to] push conventions of landscape painting and create unease or attention within the work, to promote the idea that there's more meaning to be found rather than just the enjoyment of nature.

TD: Maybe you can expand on that point of how these paintings relate or push against the tradition of landscape painting?

MB: Historically, landscape painting was using the idea of the sublime, they were allegorical. Then it became, through the Impressionists and the Group of Seven, about immediacy. To me, I've always interpreted that as using the landscape to talk about painting. The subject of the painting wasn't the landscape, the subject of the painting was the painting. I think that the landscape is so important because it's the place where all the stories happen. And my great mentor, John Scott, always described the artist as being the interior decorator for the forum of ideas. That's something I take to heart and will use the landscape to illustrate that.

TD: I like that, quote. What is your own relationship with nature? You reference climate change, what is your first-person experience been with that?

MB: We have a cottage, north of Orillia, that my grandfather built. With my kids now, it's been four generations of my family. It’s my favourite place in the entire world. I really enjoy fishing—following the cycles of where the fish are, they're not the same spot in the springtime as they are in the summer as they are in the fall as they are in the winter. That is not so predictable anymore. Even over the last 5 to 10 years. Now, that's changed. I can see it in my personal life.