By Miranda Carroll

I think it is safe to say that money is a tricky subject. We rarely talk about how a job can support an artist’s practice, how it can influence that practice, or even how it can allow for an artist to explore a fuller kind of artistic freedom excluding considerations about money. But the performance artist Bridget Moser considers that maybe “there’s something especially nice about making unprofitable decisions.” She explained that for her having a job means that she is able to make art without concern about if it is commodifiable or not.

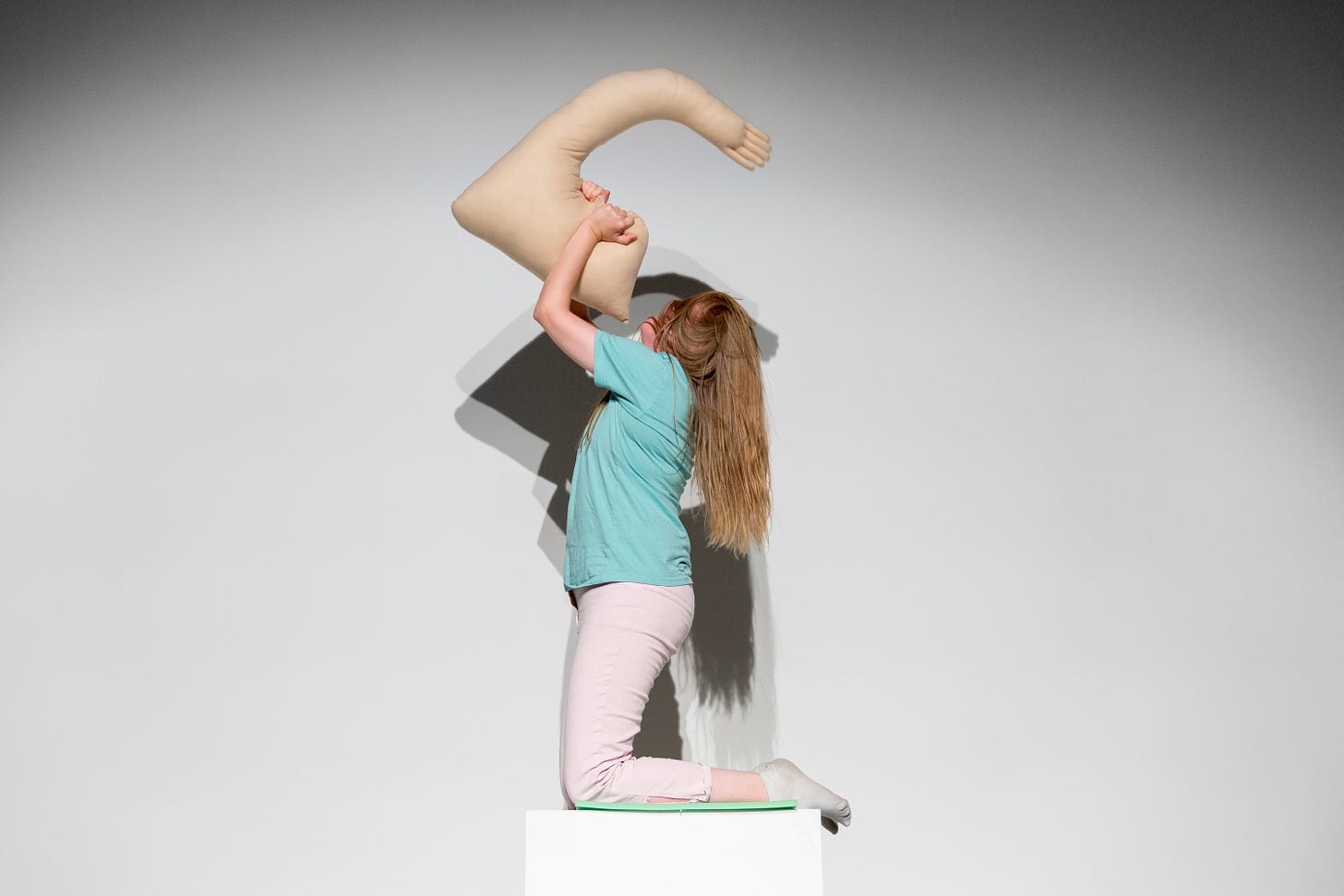

In a lot of ways, avoiding conversations like this eliminates the possibility to see the many upsides that artists find in having a day job to support their work. Sometimes it is the case that a job is not something that takes away from artistic freedom but rather something that can potentially allow an artist to produce work without significant concern over if it can make a profit. Being free of monetary considerations, as Bridget explained, can positively affect the work an artist produces. I think this can certainly be seen in Bridget’s work as she encourages viewers to question the assumed function of objects, talks through a toilet seat portal, or pushes what looks like shaving cream through the holes of a Croc.

“On a more pragmatic and less wistful note though, my job absolutely makes my artwork possible, and I realized I don’t talk about it that much, which is not intentional,” Bridget explained. You can read more about Bridget’s practice and the realities of being a working artist with a day job below.

Miranda Carroll: Tell me about your practice.

Bridget Moser: I make performances and videos where I interact with inanimate objects (for the most part regular consumer goods, but not always) using strategies you might associate with stand-up comedy, experimental theatre and dance. Each work consists of a lot of different short sequences that change abruptly and don’t really follow a narrative structure but instead create a system of common meaning or themes. Sometimes it might seem haphazard or improvised but it’s all actually scripted and, perhaps surprisingly, very labour intensive.

MC: You said in another article that you have a job. What is it?

BM: I have had my current day job for over 7 years now (all of my body's cells have been replaced by new ones in that time? incredible). I work for one of the busiest plastic surgery practices in Canada and for the most part I work from home or elsewhere if I’m traveling for exhibitions, performances, or residencies. When I started, I was mostly writing blogs and other content, but I also know how to use a lot of different design software, so I eventually started to do more design and illustration too. I’ve also learned a lot about search engine optimization so some of my time is spent on that. I also don’t mind doing whatever needs to be done in the moment, so I have hosted a talk show with surgeons and nurses at a public event, interviewed doctors and patients for videos, and appeared in social media ads when needed, among other things.

MC: How often do you work? Has your job ever impinged on your art making? How do you divide your time between your work and your practice?

BM: I usually work 3 days a week, but sometimes I work more if there is a higher volume of tasks for whatever reason. Dividing my time only feels overwhelming if I’m coming up to an art deadline, whether that’s a video shoot, exhibition opening, or performance day. There have definitely been times where I have spent all day in the gallery working on install and then have gone right back to the hotel and to finish job work until I go to sleep and maybe I have a light cry, but I also enjoy crying (Cancer sun sign). I think I’ve become better at managing my time and that scenario is less common now. What’s still common is times at home where I do my job from 9-5 and then switch to working on art until bedtime. That's not sustainable always and has also looked a lot different over the past year because of the pandemic.

I’m also lucky that the people I work for and with are really supportive of my art practice—they’ve even come to performances—so if I reach a limit (which has also definitely happened) they are understanding and accommodating. I would say, if anything, art making occasionally elbows out my job and not the other way around.

MC: Do you find there is an interplay between your job and your art? Does being in the workforce affect the kind of work you produce?

BM: Oh definitely, and probably more overtly 6 or 7 years ago. I think around then in my art practice I spent more time thinking about my own embodied anxieties, and at work I was often writing content thinking through other people’s embodied anxieties, and sometimes that overlap was more literal. I guess to some extent because my physical self is always in my work, I continue to think about that but maybe my lens has shifted a bit more to also consider how aspects of my body have shaped my experience of the world and made it easier to move through it, too.

Maybe a good thing about having a day job in a different world is being reminded that many people could not give less of a shit about the art world. I think that is a good thing, because there are many aspects of it that are, indeed, bullshit. So maybe in some ways it's helpful to me to be reminded that making work adds meaning and, to some extent, pleasure to my life, and that is what’s important to me.

MC: You have also mentioned that performance art does not pay the bills. Why do you think that is? Do you think it is harder to make money as a performance artist because of the nature of the medium?

BM: Maybe it pays some of my bills! But definitely not all of them and definitely not consistently. In that respect, I benefit from the work CARFAC has done in establishing detailed minimum fees for different kinds of exhibitions, performances, and other related activities. But I think living in an inordinately expensive city like Toronto makes it more difficult, too.

I wonder if performance is necessarily worse for income, or if painters or artists who work with other materials that have high costs have similar but different problems, especially if their practices don’t fit with the art market either. I think regardless of medium it also takes a lot of time and labour to get to a point where you have more, better-paying opportunities—not to mention the systemic barriers that so many people face on top of that—and not everyone has access to resources to be able to stick that out without burning out first. I know a lot of artists that work full time often minimum wage jobs and, in some cases, raise kids or take care of family members while still trying to make work and manage the administrative labour of being a practicing artist. It’s frankly untenable, but people do their best to make it work. I wonder if we take this for granted about a lot of the art we have in the world.

MC: How do you get funding, you mentioned in another interview that big museums pay well, how does it work now that shows are virtual? Like the most recent one you did?

BM: I sometimes get funding for production costs for specific projects through grants. And comparatively speaking, bigger institutions with larger budgets that follow CARFAC recommendations do pay better (although this wasn’t even true for the National Gallery until 2015, which seems a bit… uncool, if you know what I mean). In the past year, some institutions have done their best to create more paid opportunities for people in a virtual or other online capacity, which in my personal experience was especially true for Remai Modern and Talks Programs at the AGO. But I otherwise haven’t really participated in virtual shows—the video from my exhibition at the Remai was online during the months before the show was able to open, and late last year we did move a group video show I organized at Franz Kaka online in November as a result of the lockdown (and in that case artists were paid group exhibition fees).

MC: Would your art making be possible without your job, how much of a discrepancy is there?

BM: It might be possible (probably not haha) but if so, my work would almost certainly look really different. I don’t think I would be very happy. I like making the work that I want to make, where I don’t have to spend one minute wondering if one decision will be more profitable than another. Maybe there’s something especially nice about making unprofitable decisions. One thing I like a lot about performance is that it wasn’t designed to be commodifiable. Now that we're one year into the pandemic, I feel very intensely that the liveness of live work is actually the most incredible thing. Like, being in a room with someone doing something, just for a little while, can be very exhilarating. God, what I would give to be in a room with someone doing something, just for a little while!

On a more pragmatic and less wistful note though, my job absolutely makes my artwork possible, and I realized I don’t talk about it that much, which is not intentional. I’m now at a point where things have come full circle and I’ve led a residency at the Banff Centre for emerging artists. I talk to and DM with artists in early phases of their practices all the time, and I think many of them feel a lot of pressure to follow a specific trajectory that they feel needs to include an MFA, commercial gallery representation, and either an academic job or no job at all. Those are not things that I have or want. In some ways it feels important to say: I understand that pressure, and I know those things work really well for some artists, but if those things don’t work for you—and there are many, many reasons why they may not—that’s also okay, if not a good thing in its own right. If making work adds meaning and, to some extent, pleasure to your life, then it’s worth doing.

MC: Do you ever see yourself as doing your performance art full time?

BM: That could be cool! But, realistically, no I don’t see that. I can’t afford a studio or an RRSP (sorry to my parents who have anxiety about this) even with my job. I believe very strongly in universal basic income, but we can’t even get pharma care in Canada and CERB payments are somehow contentious to many, so that seems like a distant dream.

I do like my job and I think that’s a fortunate position to be in. Maybe I even love my job, somewhat?? In a dream world, though, of course, I would love to spend my time inhabiting and expressing my own life. But while I wait for that day, if anyone ever wants to talk about work/life/art balance, my DMs are open. And—fully legitimately also—if anyone ever wants to talk about plastic surgery or non-surgical procedures in a judgment-free zone, my DMs are equally always open. We can also contain multitudes.

Miranda Carroll is completing her undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto majoring in Art History and English Literature. Originally from Hamilton, she now lives in Toronto. In addition to her studies, Miranda has written and illustrated for the Victoria College newspaper and The Hamilton Review of Books. Graduating in May, she is excited for whatever the future holds.

You can follow Bridget Moser on Instagram here.

I think it’s a big mistake thinking you can pay the bills with your art practice from the get go.Find a steady income then you are definitely free to do what ever you love. Giving my work to charities and friends is far more rewarding to me than receiving money for it. I am a carpenter which is a great way to dovetail my work and art.